Mystery tooth linked to Paul Gauguin

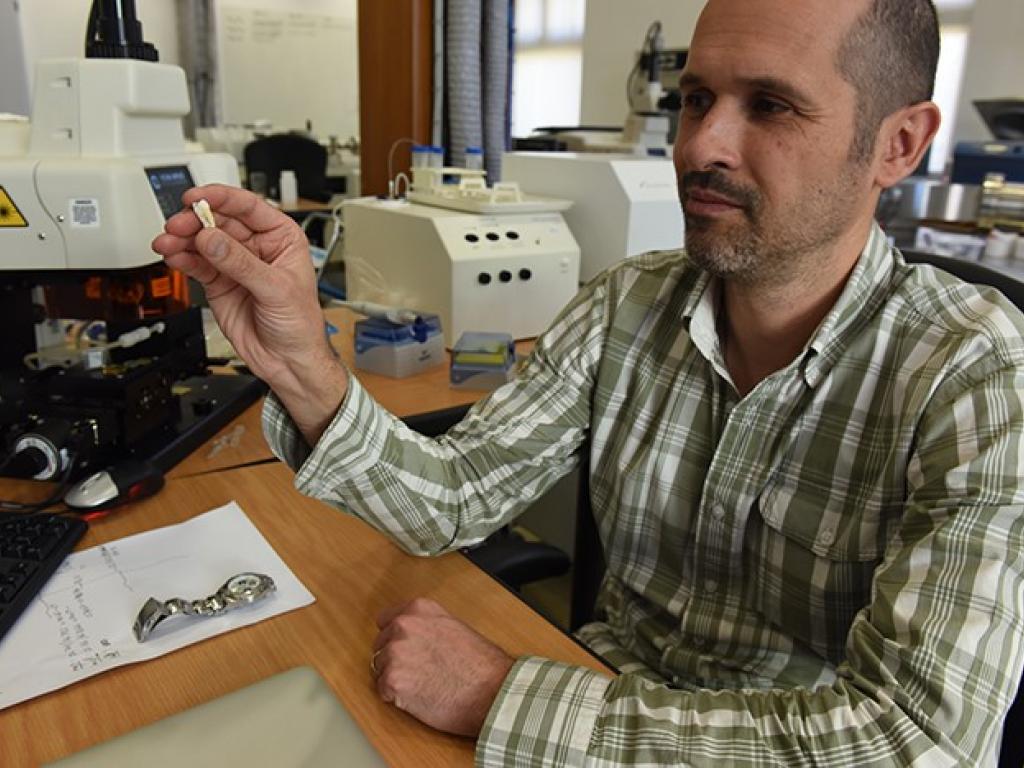

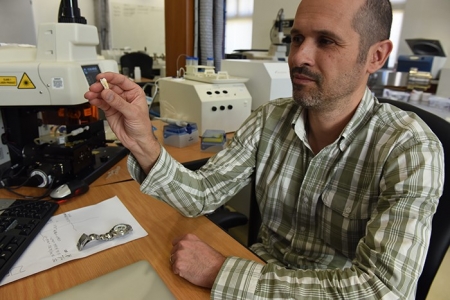

Dr Petrus le Roux, the head of geological sciences’ radiogenic isotope laboratory, examines a molar that likely belonged to French artist Paul Gauguin.

When a University of Colorado – Boulder professor contacted Dr Petrus le Roux to analyse a tooth thought to have belonged to French artist Paul Gauguin, the UCT geochemist thought he was being jibed. But it’s not the geochemist’s first unusual assignment.

Le Roux heads up the Department of Geological Sciences’ radiogenic isotope laboratory, which provides a multi-purpose isotope analysis service for solutions and solid materials, particularly rocks and minerals.

Increasingly, it’s become a go-to facility for strontium isotope analysis for projects from fields as diverse as archaeology, palaeoanthropology, zoology, botany and environmental and climate studies.

“We do quite a lot of strontium isotope analysis for palaeo-science projects, from Later Stone Age Western Cape projects to Cradle of Mankind hominin teeth,” says Le Roux amid the hum of high-tech machinery in the laboratory. “It’s the only analytic facility in the country that can do this. It’s become something of a centre of excellence.”

Samples are pouring in from around the world: hair from Andean mummies found in the Atacama Desert, ivory from an extinct elephant on Sicily and dinosaur teeth from Alaska.

And just last week, a molar thought to have belonged to Post-Impressionist artist Paul Gauguin. It’s one of his more unusual assignments, says le Roux.

Reading the teeth

Gauguin was born in France, but when he was two his family went into exile in Lima, Peru (his mother was Peruvian; his father, Clovis, French. Sadly, Clovis died on the voyage). Gauguin spent his early childhood in Lima before moving back to France.

Later, eschewing the strictures of European life, Gauguin spent his last days living and painting on the remote French Polynesian islands of Tahiti and the Marquesas. He died on Hiva Oa in the Marquesas in 1903.

In 2003 four teeth were found on Hiva Oa in a glass bottle at the bottom of a well on the site where Gauguin’s house once stood. Enter historian Dr Caroline Boyle-Turner (PhD Columbia University), an art historian living in France and a Gauguin expert who founded and directed an art school in his village of Pont-Aven.

Boyle-Turner was working on a book, the recently released Paul Gauguin and the Marquesas: Paradise found? She happened to arrive on Hiva Oa as the mayor was contemplating the objects dredged from the well. He asked her to compile and inventory the scores of items found, which included the teeth.

“I was curious if they really were Gauguin’s teeth,” writes Boyle-Turner “and decided to go further than DNA testing. If they were his, did they contain traces of mercury or arsenic? These were both treatments for syphilis at the time, a disease many thought Gauguin suffered at the time.”

Closer to the truth

Boyle-Turner reports that a study coordinated by Dr William Mueller, a team of dentists and University of Chicago forensic scientists found no traces of heavy metals. And the teeth had deteriorated so much that a DNA match with Gauguin’s Tahitian grandson, Marcel, proved inconclusive.

“The plot thickened when news of the DNA testing was published in The Art Newspaper,” Boyle-Turner reports. “A team of scientists and grad students in Chile picked up the story. They were excavating a seaside graveyard in Patagonia and had found several bodies of South Americans and one of a European male.”

Was it the body of Clovis Gauguin who’d died en route to Peru?

Boyle-Turner was contacted and a dialogue ensued between France, Chile and Chicago.

“This resulted in the discovery that the DNA of the body proved to be a match with that of Marcel Gauguin,” she reports.

A detailed scientific study will be published next year. Le Roux’s findings have been crucial, says Boyle-Turner.

“The discoveries made just last week in South Africa offer further proof of the identity of the teeth found in Hiva Oa, proof that Marcel really is the grandson of Gauguin and that the body found in Chile is really that of Clovis Gauguin.”

The molar, with a “humongous cavity”, was found among remains at the bottom of a well on Hiva Oa in the Marquesas Islands where Paul Gauguin spent his last years.

Strontium isotope signatures

On receiving the mysterious tooth (“It had a humongous cavity!”) and his brief, Le Roux confesses that he was sceptical at first.

“I never like doing stuff when the investigators are not here because I have to decide where to analyse. But we got a very interesting result.”

He tested the enamel on the crown, the sides and the root of the tooth, a relatively quick procedure using the lab’s laser ablation MC-ICP-MS instrument.

The enamel played a vital role in linking the tooth to Gauguin and his early years in Lima.

Radiogenic strontium isotope signatures in human tooth enamel can be used to reconstruct all kinds of scenarios, such as geographic origins and migratory patterns. They can also be used to distinguish whether remains found at archaeological sites are from local or non-local people.

Adult teeth form in a very systematic way and the enamel in this mystery tooth was created in the first two to seven years of this person’s life, says Le Roux. Furthermore, strontium isotopes in tooth enamel mirror that of the soil, plants and water of the region due to one’s diet in early childhood.

“They [the researchers] didn’t tell me what value they were expecting and I didn’t know what to expect,” said Le Roux.

Armed with his results, he went in search of strontium isotope values for Peru. He was in luck. Google led him to Andean strontium isotopes of Peruvian soils for palaeo-mobility sites.

“And lo and behold, the strontium isotope range for Lima is quite different from the rest of Peru – and the value we got for this tooth. The values all agreed with each other and are smack bang in the middle of the range for Lima, where Gauguin spent his early childhood.

“They were very excited when I sent the results.”

Large studies in Chile and Argentina

Le Roux and his team are involved in a number of other international projects with researchers across the world. But South America, particularly, is yielding some interesting work.

Le Roux reports more and more sampling coming from Chile and Argentina. Researchers in Argentina are conducting a massive study from Mendoza over the Andes to the Pacific, as well as a large bio-available strontium isotope map of northern Chile.

“The very early pre-Mayan and pre-Inca communities that lived in the region are a big focus for researchers.”

Story Helen Swingler. Photo Michael Hammond.