Harnessing plant power to curb COVID-19

Cape Bio Pharms, a biotech company with its origins in the UCT Biopharming Research Unit, is harnessing a distant relative of the tobacco plant (pictured) in the global effort to create a fast and affordable antibody test for COVID-19.

Here’s a different reason for tobacco to be in the news. Cape Bio Pharms, a biotech company with its origins in the Biopharming Research Unit (BRU) at the University of Cape Town (UCT), has joined the global effort to create a fast and affordable antibody test for COVID-19, using a relative of the tobacco plant.

The team of scientists that works at the company is using Nicotiana benthamiana as a bioreactor to produce COVID-19 proteins and antibodies. They are working towards developing components of a serology test for the disease, which detects antibodies in a patient’s blood and can be used to see if they have been exposed or previously infected.

Access to locally produced research reagents like this, which are safe and reliable, strengthens the position South African scientists in global biotech innovation, says Cape Bio Pharms’ Tamlyn Shaw who co-founded the company with her mother, Belinda Shaw, in 2018 as a way to commercialise the biotech innovations developed by the BRU.

“At the moment, our scientists rely on imports of these products, which costs a lot of time and money. The easier it is for them to secure a sustainable supply of locally manufactured proteins, the more medical innovations we’ll be seeing from our shores.”

“The research and development that results from reliable reagents are what can contribute to fighting pandemics and eventually saving lives.”

Making proteins and antibodies in plants

Associate Professor Inga Hitzeroth, a biotechnologist at BRU, explains that they have been using N. benthamiana in their research for over 20 years because of the plant’s strength and ability to grow quickly.

She and her colleagues – like others around the world – essentially harness the plant as a small factory to produce proteins and antibodies that they can later extract for use in vaccines and diagnostics. The scientists do this by ‘infecting’ the plants with an engineered soil bacterium that transfers DNA to the plants and induces them to produce proteins known as antigens from that genetic information.

“When they are about six weeks old, we infiltrate the plants with bacteria that encode antigens (substances that provoke an immune response in animals and people). The plants then start producing the proteins,” she explains.

Professor Ed Rybicki, virologist and director of the BRU, explains that what makes plant-produced proteins and antibodies particularly useful is the speed with which they can be generated: from seed to extraction can take a matter of weeks.

By comparison, when using mammals like rabbits or sheep in the same way, the process can take months to half a year.

Another advantage that doesn’t apply to animal-made antibodies, Rybicki notes, is that batches of plant-based reagents are derived from the same genetic construct, standardising the results.

This consistency helps scientists produce dependable biomedical tests, says Tamlyn Shaw, which fast-track the development of new medicines, vaccines and diagnostics.

“The research and development that results from reliable reagents are what can contribute to fighting pandemics and eventually saving lives. As we are seeing now with COVID-19, time is essential when fighting outbreaks,” she says.

Joining the fight against COVID-19

To tackle COVID-19, the team at Cape Bio Pharms first sourced the gene sequences for the virus, SARS-CoV-2. Then they launched Plants Against Corona: a global partnership of commercial research labs and academic partners around the globe.

“Building global networks today helps the world prepare a first line of defence against the next pandemic.”

Following this, the Cape Bio Pharms team developed the DNA constructs encoding antigens that they used to infiltrate the plants and turn them into mini bioreactors.

These antigen constructs are an essential component of global efforts to create both diagnostic tests and a vaccine for COVID-19. And the antigens created by Cape Bio Pharms have been shared with the Plants Against Corona network to be used by researchers around the world.

“We have already sent samples of our antigens to local test-kit manufacturers who are validating our proteins externally. These proteins have passed our own internal validations and tests, and one of the test-kit manufacturers has confirmed our protein has been clearly recognised by antibodies against the virus,” says Tamlyn Shaw.

Local solution to a global need

Belinda Shaw, Cape Bio Pharms’ CEO, explains that two types of testing are needed together to pick up different aspects of COVID-19 at the genetic level: serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

Serology testing is unlike most diagnostic COVID-19 tests, which look for genetic material from the virus to see if someone is currently infectious.

“Once a person is producing antibodies, we know they’ve recovered, but not necessarily developed immunity to the virus,” she says. “Serology testing allows for continuous assessment of those who have resumed work and social-care duties.

“The speed and accessibility of these test kits will allow public health authorities to consistently test for SARS-CoV-2 in their communities.”

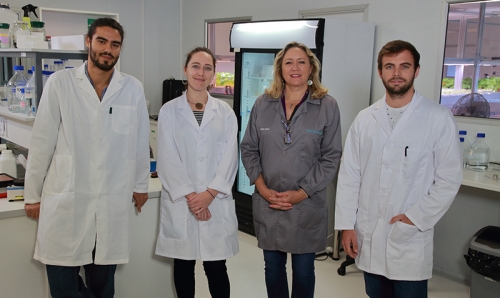

The team at Cape Bio Pharms (left to right): Francisco Pera, head of upstream research & development; Tamlyn Shaw, co-founder and chief scientific officer; Belinda Shaw, co-founder and CEO; Scott de Beer, head of downstream research & development. Photo supplied.

The need for biotech

While time is of the essence in the current COVID-19 crisis, the team also takes a long-term view of the role of plant-produced antibodies in research.

UCT researcher Dr Ann Meyers, based at the BRU, explains that the techniques being harnessed against COVID-19 also have applications far beyond this virus.

“At the BRU, we work on creating antigens and vaccines for a wide range of diseases that affect both humans and animals. These include everything from HIV-1 and HPV to other diseases like the Rift Valley fever virus and bluetongue virus, which infect sheep.

“By creating affordable diagnostic tests, we can help local researchers to better understand the incidence of these diseases in Africa. The BRU is also an essential incubator for highly-trained researchers who understand this work and who go on to create important research networks across the continent.”

Belinda Shaw agrees: “Building global networks today helps the world prepare a first line of defence against the next pandemic. Taking history into consideration, we can be sure of one thing: COVID-19 won’t be the last.”

The advantages of spin-off companies

“Spin-off companies, like Cape Bio Pharms, benefit UCT in a number of ways,” says Dr Andrew Bailey of UCT Research Contracts & Innovation.

“They enable research outputs to be commercialised to maximise their impact. They create local jobs for highly-skilled postgraduate students, like those from the BRU in this case. And they reward the UCT intellectual property creators with a share of royalty revenue. The other revenue that UCT derives is ploughed back to support further research and innovation initiatives.”

“Furthermore, spin-off companies allow researchers to pursue, through their research, a pipeline of technologies that they know the company is interested in commercialising. This strengthens opportunities to attract funding.”

Story: Ambre Nicolson

Photo: Charles Andrew, WIKIMEDIA.