A safari across the African savannah and into the Cape

Prof Muthama Muasya’s research focuses on the taxonomy and evolution of plants with a special emphasis on Africa and the Cape region. Photo Supplied.

As the continent prepares to draw the curtain on Africa Month, the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Professor Muthama Muasya took to the virtual stage to present an inaugural lecture fitting for the time, and suited to the continent.

The lecture, titled “Biodiversity studies in the Anthropocene: from species discovery in fragmented landscapes to unravelling the origin of iconic African flora” was hosted by UCT Vice-Chancellor Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng on Wednesday, 26 May. The dean of the Faculty of Science, Professor Maano Ramutsindela, and the head of the Department of Biological Sciences, Associate Professor Tony Verboom, were also in attendance.

“It’s humbling to have been invited to talk to you this evening. I find it a good coincidence that I am speaking about biodiversity and African heritage in the week and month that we are celebrating Africa, and where the theme for this year is ‘Africa’s arts, culture and heritage’,” said Professor Muasya, referring to the African Union’s 2021 Africa Day theme.

Now a full professor of biological sciences, Muasya’s research focuses on the taxonomy and evolution of plants with a special emphasis on Africa and the Cape region. A recurring theme in his research relates to documenting the region’s diversity and seeking explanations to what underpins the evolution of plants over space and time. During his lecture, he discussed species discovery in the Cape flora, and presented several highlights on the evolution of the African savannah known as the Cradle of Humankind.

“Africa has a rich biodiversity, whether it’s ecosystems, species kinds or species variations.”

“Africa has a rich biodiversity, whether it’s ecosystems, species kinds or species variations. Five major biomes occur [and] the vegetation is determined by rainfall, temperatures, seasonality, elevation and soils,” he said.

African savannah

The African Savannah ecosystem is a tropical grassland with year-round warm temperatures, and distinct wet and dry periods. The savannah is characterised by grass and small or dispersed trees that do not form a closed canopy and allows sunlight to reach the ground.

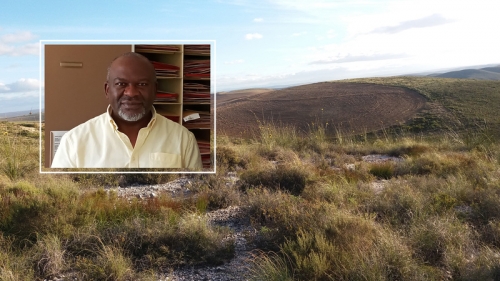

Prof Muthama Muasya explained that savannahs thrive in both mesic and arid environments. Photo Javier Puig Ochoa / Wikimedia Commons.

According to Muasya, savannahs thrive in both mesic and arid environments. However, he explained, these patterns are sometimes transitional and are often dependent on elevation, soil and how frequently fires occur in the region.

“The African savannah support a wide range of browsers – animals that feed on leaves using their tongue. But the browsers’ damage [to trees has been] reduced [as a result of] plants bearing thorns,” he said.

Some of the savannah’s most notable features include acacia trees and spiny plants. However, the presence of spiny bushes is “relative to vegetation type” in the area, and their survival depends on the amount of rainfall that occurs in the region.

Muasya said that his research also indicates that non-spiny bushes species have “gradually accumulated” in the savannah over time. But spiny plants have been around for more than 40 millions years, and increased exponentially about 20 million years ago. The number of bovid animals who call the savannah home also increased dramatically – similar to the spiny plants in the region.

“African savannahs originated [during] the Miocene [epoch], but their [current] features may be in response to different drivers,” he said.

Cape flora

The process to identify and document the world’s biodiversity has progressed over the past 300 years and herbarium (: the process of preserving pressed plant species with accompanying field data) plays an essential part in this process. “The collection of herbarium specimens in the Cape began in the 1600s,” said Muasya.

He further explained that UCT’s Bolus Herbarium, which includes the Bolus Herbarium Library, was bequeathed to the university 150 years ago and is the oldest functioning herbarium in South Africa. With close to 500 000 specimens, the herbarium boasts one of the largest university collections in the world. In the past decade alone it has played a significant role in helping scientists understand the Cape flora.

Muasya pointed out that flora found in southern Africa has a complex biogeography, built in response to a range of drivers. He focused part of his lecture on the Eastern Overberg Renosterveld – one of the most unique vegetation types in the Cape Floral Region. He said that this vegetation is “highly fragmented” by agriculture and has produced a number “novelties” recently. The quartz habitats in the region host more than 25 narrow-ranged species among 70 red-listed species. Furthermore, the Cape fynbos also contributed to and received taxonomy from other biomes and received long-distance dispersal all the way to Australia.

“In the words of the African theologian and philosopher Professor John Mbiti, ‘I am because we are and, since we are, therefore I am’.”

Muasya said he remains humbled and privileged to serve diverse communities of practice and to contribute to taxonomic plant science expertise in Africa.

“In my journey I have [received] knowledge and goodwill from others and I enthusiastically share it. In the words of the African theologian and philosopher Professor John Mbiti, ‘I am because we are and, since we are, therefore I am’,” he said.

Story: Niemah Davids