Water in the Anthropocene in South Africa

Without public engagement, South Africa will continue to face serious water threats that will compromise long-term human and environmental health.

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), the global water crisis is one of the greatest threats to humanity. As South Africa’s National Water Week continues and World Water Day draws near, Dr Kevin Winter from the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Future Water Institute considers the critical information available from our national water risk data.

The Anthropocene is a modern-day geological epoch in which humanity has become the major driving force behind changing earth systems from conditions of relative stability, during interglacial Holocene period that began 11 000 years ago, to the great acceleration period of relative instability (Steffan et al 2004). The results of these changes are observed in the natural disasters we experience more and more frequently – droughts, fires and floods.

The repercussions of these events for humanity, and an environment with limited capacity to recover from these shocks, have resulted in involuntary migrations that are not only politically motivated. The ability to remain resilient while dealing with disasters is partially explained by the state of natural resources that are pushed beyond their planetary boundaries (Rockstrom et al 2014).

“The global water crisis [is] one of the ten greatest threats to human development.”

The freshwater cycle boundary is strongly affected by climate change, but water demand and use are the dominant factors that determine the supply and quality. The WEF consistently ranks the global water crisis as one of the greatest threats to human development and likelihood of occurrence (WEF 2019). The assurance of water supply and access to support 9 billion people by 2040 will one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century (UN 2019).

Water stress in South Africa

While global attention is focused on the devastating effects of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), World Water Day on Sunday, 22 March, is an opportunity to remember that water resources remain one of the biggest global risks. For South Africa, the predicted 17% shortfall in water supplies by 2040 is an imperative that has to be addressed, but so too is the urgency to reverse declining water quality (Hedden and Cilliers 2014).

Supply issues have dominated government programmes for decades, but too little attention has been given to building capacity to adapt to fast-changing, disruptive conditions. Decisive action is needed – something like the government’s programme to manage COVID-19. We are missing the urgency in the water sector.

Small signs, which appear insignificant now, will have significant repercussions in the future. For example, in South Africa slow but significant changes are observed in declining surface water flow and irreversible damage to ecological systems. Researchers have noted that for every 10% of land that is altered in a catchment, the result is a 6% loss in freshwater biodiversity (Dallas and Rivers-Moore 2014).

“Small signs, which appear insignificant now, will have significant repercussions in the future.”

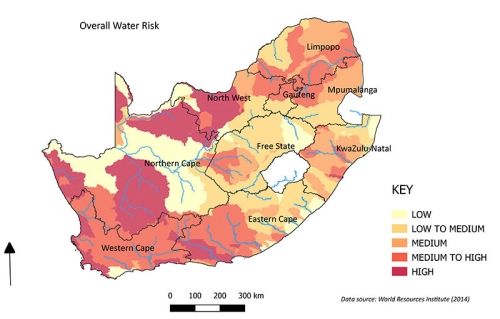

The water stress map of South Africa below (Figure 1) identifies areas with exposure to water-related risks. The data is calculated from an aggregation of physical quantity, quality, regulatory and reputational risk categories published by the World Resources Institute. It accounts for 12 factors, including seasonal and inter-annual rainfall variability, flood occurrence, drought severity, groundwater stress, access to water, and threatened amphibians. The highest water risks are found in the Western, Eastern and Northern Cape provinces. It shows an imbalance in the annual water withdrawal by municipal, industrial and agricultural sectors against the annual available rainfall and storage capacity.

Drought severity and inter-annual variability of rainfall are not the only reasons for the water crises in the Western Cape and the Eastern Cape. There are other risk factors that often escape public interest, such as environmental risk resulting from poor water quality. Fragile freshwater ecosystems are found in catchments where there are excessive water withdrawals, poor water quality from surface water runoff and poorly performing sewerage works.

Figure 1: A composite indicator map of water risk in South Africa.

Institutional and public capacity

Water is crucial for building the resilience of humanity and the support of ecosystems. Both are necessary and are managed by integrating blue water (rainfall) and green water (intercepted by plants and soil) into land-use practices, especially in river-basin catchments.

Effective land management in South Africa’s nine catchments is in a state of inertia, with only two catchment-management agencies in a position to effectively regulate water use and planning. The water risk map highlights the potential danger of focusing on the physical risks of water supply in a catchment area, but fails to deal with the risk to vulnerable ecosystems, including access to clean water and reputation damage to water management authorities and, consequently, public mistrust in the ability of the government to manage water resources..

There is no current South African map of institutional capacity for water management. If there was, it would identify further gaps and constraints in institutional capacity for integrated water resource management. This capacity was highlighted in a recent report commissioned by Corruption Watch entitled Money Down the Drain: Corruption in South Africa’s Water Sector, which explored the extent of corruption in the water and sanitation sectors and made several recommendations for actions to address maladministration. The report calls for an end to impunity and to instil a culture of accountability and ethical and committed leadership.

“On World Water Day, our strength is in exercising our democratic and constitutional rights.”

On World Water Day, our strength is in exercising our democratic and constitutional rights. There is no let off. Citizens continually need to expose corrupt activities and ensure that remedial actions are taken to address deficiencies. Without public engagement, South Africa will continue to face serious water threats that will compromise long-term human and environmental health.

While we definitely learned from the threat of Day Zero about how to work together in a crisis, and we will, no doubt, learn similar lessons in defeating COVID-19, we are not learning much from the signals that we are getting from our national water risk data. COVID-19 has already overshadowed South Africa’s National Water Week, but in these troubled times it is worth remembering that water is critical to the survival of humanity and the environment.

References

Steffen W, Persson A, Deutsch L, Zalasiewicz J, Williams M, Richardson K, Crumley C, Crutzen P, et al. 2011b. The Anthropocene: from global change to planetary stewardship. Ambio 40: 739–761. DOI: 10.1007/s13280-011-0185-x www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3357752/.

UN. 2019 World Population Prospects 2019, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations Population Dynamics Division www.population.un.org/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2019_Highlights.pdf.

Rockstrom, J. et al 2014.The unfolding water drama in the Anthropocene: towards a resilienceâbased perspective on water for global sustainability, Ecohydrology, Vol 7 5 p1249-1261 www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/eco.1562.

Helen F. Dallas and Nicholas Rivers-Moore 2014 Ecological consequences of global climate change for freshwater ecosystems in South Africa S. Afr. j. sci. vol.110 n.5-6 Pretoria Mar. 2014 www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0038-23532014000300010.

Parched prospects The emerging water crisis in South Africa Steve Hedden and Jakkie Cilliers, Institute for Security Studies https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/AF11_15Sep2014.pdf.

World Resources Institute www.wri.org/aqueduct.

Story: Kevin Winter

Photo: Flickr