Discovery of new ocean current underpins PhD

PhD candidate and physical oceanographer Juliano Ramanantsoa’s paper reveals details of the new ocean current that he and his co-authors discovered off south-west Madagascar, his home island.

It’s not often that PhD research makes world news. Doctoral candidate Juliano Ramanantsoa’s discovery of a new current off south-west Madagascar has rounded off his doctoral research – and brought him and his co-authors international commendation.

The Southwest Madagascar Coastal Current (SMACC) was described in Ramanantsoa’s recent journal article in Geophysical Research Letters.

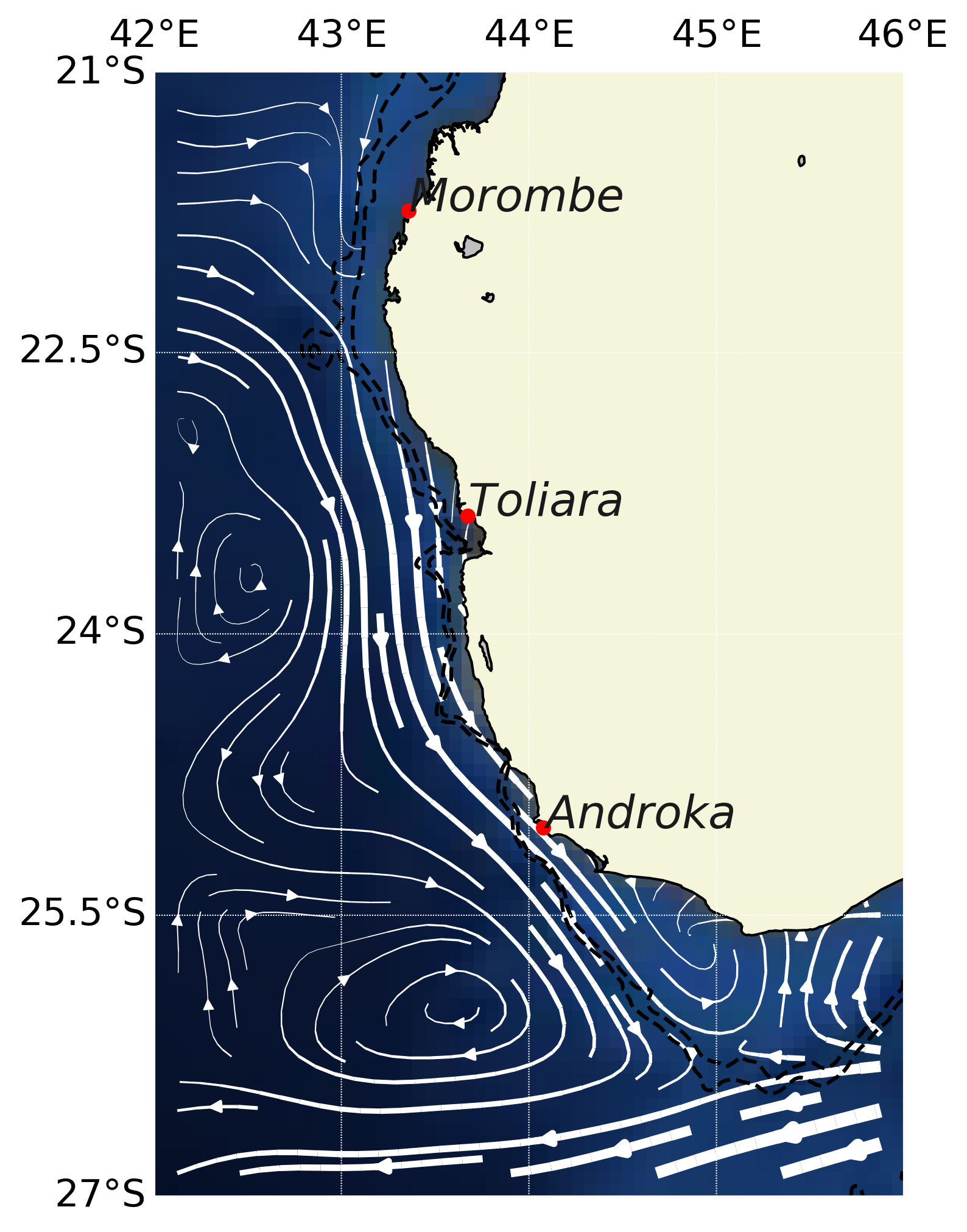

According to the observational-system and computer-modelling data, this wind-driven, poleward- flowing surface current is relatively narrow and shallow – some 300 metres deep and 100 kilometres wide – and salty.

It flows more intensely in summer, and its physical impact on the ocean is particularly noticeable in a rich upwelling of nutrient-dense waters at the southern end of Madagascar. This has implications for the commercial and subsistence fisheries in the region as well as for the Agulhas Current along South Africa’s eastern shores.

The current transports an average of 1.3 million cubic metres of water a second, and is comparable to the poleward-flowing Leeuwin Current off western Australia.

Mysterious upwelling

Initially it was the mysterious variability in the ocean upwelling off the south-western part of the island that puzzled Ramanantsoa, a Madagascan national. He was unable to ignore it as his PhD needed to account for the phenomenon.

“The only explanation was a poleward, warm surface current moving to the southern tip of Madagascar, which influences the upwelling.”

The researchers analysed a battery of data: shipboard observations (water speed and direction, salinity, depth and temperature), satellite observations of sea surface temperatures, surface drifter trajectories from Global Drifter data, and a computational model of ocean dynamics in the region.

The analysis proved their hunch: they were dealing with a previously unknown, warm surface current heading south towards the pole. The water wasn’t emanating directly from the East Madagascar Current but from the Mozambique Channel, the 400 kilometre stretch of ocean between the island and the Africa mainland.

Global ocean systems

Besides the broader implications for understanding global ocean systems, the impact of the current’s discovery adds significantly to studies on the greater Agulhas Current system, which has its sources in the East Madagascar Current and the Mozambique Current.

It also provides a bigger picture for fisheries.

“Big fisheries [on the island] blame the seasonal scarcity of fish on the subsistence fishers. My work has suggested that production variability is not the fault of small fishers; it’s the current that varies and affects the fisheries. So, understanding the current helps with planning.”

Building regional resources

The discovery was a major boost for Ramanantsoa’s PhD, which is due for hand-in soon. With master’s degrees from the Institute of Halieutics and Marine Science at the University of Toliara, in his home town in the south of Madagascar, and the University of Reunion Island under his belt, Ramanantsoa came to further his studies at UCT in 2015.

It was a strategic decision. For a career as a physical oceanographer or an academic in the field he’d need a bigger stage than his home island. He chose UCT for its publications record, infrastructure and resources.

“And it’s not far from my home! It’s also a country [South Africa] that cares for the South Indian Ocean, and this is my focus; I want to learn more about the waters surrounding Madagascar, including the south-west Indian Ocean.

Ramanantsoa has spent half of his time in France; he has two supervisors in France and two in South Africa – one at UCT and the other at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research.

He is immensely gratified by the Faculty of Science scholarship that gave him wings. His research and the network of collaborators he has developed will help him boost oceanographic resource development back on Madagascar, with its 5 000 kilometres of coastline.

“I realised we still need to learn a lot about our oceans and currents [in Madagascar], but we don’t have the skills or resources for physical oceanography.

“I grew up at the sea,” he says. “At school, like every kid in town, I’d drop off my bag and go to the sea until dark. It’s so hard not to experience that intimacy with the ocean. It was my entire life. Every day was a holiday.”

“I grew up at the sea. At school, like every kid in town, I’d drop off my bag and go to the sea until dark. It’s so hard not to experience that intimacy with the ocean. It was my entire life.”

Planning to sign up for a postdoc at UCT once he has handed in his PhD, Ramanantsoa will work with his supervisors to develop physical oceanography in the region around his “marginalised island”.

“Very few studies have been interested in doing this before. It’s been neglected and we’ve lost a lot of information from the past.”

His postdoc studies will extend his focus on the seas off the south of the island, but specifically on the south-eastern side.

“This is a huge, well-known current, but it’s unstable and highly exposed to climate change. I want to understand its dynamics. It’s also one of the main contributors to the Agulhas Current.”

In the long term he’s hoping to build a physical oceanography laboratory in his home town on Madagascar and further develop links between the two countries.

“We can’t work alone. We need to support each other. Science doesn’t have any borders.”

Read the article in Geophysical Research Letters...

Ramanantsoa’s supervisors are Marjolaine Krug (Council for Scientific and Industrial Research), UCT’s Professor Mathieu Rouault (Department of Oceanography and the Nansen-Tutu Centre for Marine Environmental Research), Dr Pierrick Penven (Institute of Research for Development, Brittany), and Jonathan Gula (University of Western Brittany, Brittany).