The universe in a cloud

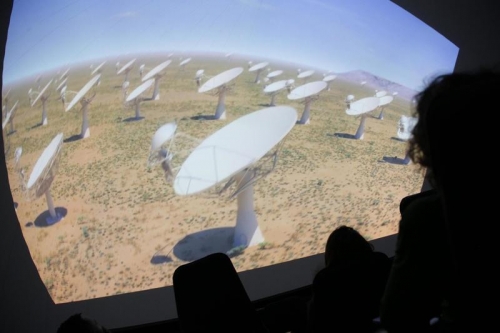

Audience watches an animated short about how data is collected from MeerKAT telescope in Carnarvon in the Karoo and rushed to Cape Town to be processed on the IDIA research cloud.

The MeerKAT telescope, the first phase of the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) telescope in South Africa, will allow astronomers to understand how galaxies form and evolve, study dark matter, black holes and understand some of the most violent explosions taking place in the universe. The trouble is that before we can unlock these secrets of the universe, we have to solve the accompanying big data challenge.

“The MeerKAT is an amazing instrument with fantastic science goals,” says Professor Russ Taylor, director of the Inter-university Institute for Data-Intensive Astronomy (IDIA) and SKA research chair at UCT and the University of the Western Cape (UWC). “The catch is that the answer to these and other questions about our universe lives in a massive stream of data.” Unless scientists can develop the tools to work with data on that scale, the universe will remain a mystery.

Speaking at the launch of the IDIA research cloud at the Iziko Planetarium and Digital Dome on Monday, Taylor said that the massive data sets to be produced by the MeerKAT and then the SKA is the biggest ‘big data’ challenge in science – and that challenge starts in South Africa.

“We have a window of opportunity here with the MeerKAT – as a South African instrument – before the world converges on us,” he says. IDIA, a partnership of three South African universities (universities of Cape Town, the Western Cape and Pretoria) is working to build the solutions to the SKA big-data challenge here, so South African researchers can own the data and make the scientific discoveries.

The IDIA resesarch cloud

The IDIA research cloud is the first step toward that goal. IDIA’s computer cloud is tailored to process data on a scale expected from MeerKAT. Beyond just the storage for the raw data, the cloud computing facility allows researchers to use their own tools to process data on unprecedented scales.

Scientists use computer algorithms to build analysis pipelines, turning data into images and to analyse and visualise the data to create new knowledge. On the IDIA research cloud, they can deploy pipelines and analytics that they have already built, and run special programs to visualise and explore the data.

“The size of the data produced by MeerKAT means we need to change the way we do science: the IDIA research cloud will allow us to do that.”

The IDIA cloud technology democratises high-performance computing and makes big data accessible to researchers anywhere. The IDIA cloud software systems are also all built on open source technologies so these tools can be re-used and recreated in other disciplines.

“The size of the data produced by MeerKAT means we need to change the way we do science: the IDIA research cloud will allow us to do that,” says Dr Sarah Blythe of UCT, principle investigator on the LADUMA project of the MeerKAT.

Research on the IDIA Cloud

Without the IDIA research cloud, says postgraduate researcher Wathela Alhassan from UWC, he would be unable to conduct his research. “With the cloud, I can build multiple models with different set ups and architecture and run them at the same time to see which one is better,” he says. “Having access to this much computational power for free is an opportunity I could not even dream of.”

“With the cloud, I can build multiple models with different set ups and architecture and run them at the same time to see which one is better."

Hassan will be using the MeerKAT data to look for unusual or unfamiliar phenomona in the data that may indicate intelligent life on another planet.

“Basically I will be using the IDIA cloud to look for aliens,” he says.

Large science projects like SKA have knock-on effects for the society in which they take place. They stimulate technological advancement, such as the IDIA research cloud, which are then re-used in other disciplines and even industry. A range of scientific disciplines are also facing the big data challenges. Astronomers are among the main users of this cloud right now, but other disciplines – like health and medical research– will benefit from the infrastructure too, hopefully using it to solve some of the wicked problems faced by the world today.

The IDIA research cloud will be a key instrument to the scientific exploration of MeerKAT data. Of the eight large survey projects conducted on MeerKAT, five of those are led by scientists in IDIA partner universities and will use the IDIA research cloud.

These are:

- The MIGHTEE (MeerKAT International GHz Tiered Extragalactic Exploration) project, looking at very distant galaxies, seeks to understand how galaxies form and evolve over the history of the universe.

- The MHONGOOSE (MeerKAT Observations of Nearby Galactic Objects – Observing Southern Emitters) study will be mapping hydrogen gas in the relatively nearby galaxies. Because hydrogen gas is nearly everywhere in the universe, the mapping of this gas will unveil intimate details of galactic and stellar phenomena.

- The LADUMA (Looking At the Distant Universe with the MeerKAT Array) project will focus on hydrogen in the distant universe, looking at how hydrogen gas was distributed nearly 8 billion years ago, when the universe was less than half its current age.

- Galaxies don’t form or exist in isolation: groups of galaxies are bound together by gravity. Fornax is a one such of group of galaxies that the MeerKAT telescope has a very good view of. The Fornax Survey will study this cluster and the interaction between the galaxies within it.

- The ThunderKAT (The HUNt for Dynamic and Explosive Radio transients with MeerKAT) project will study the most powerful explosions of the universe. Some of the most violent explosions in the galaxies are not yet fully understood, taking place in conditions of extreme temperature, pressure, gravity, acceleration and other conditions simply impossible to recreate. The ThunderKAT team could well discover something we have never seen before.

Story: Natalie Simon

Photo: Michael Hammond