Ledumahadi Mafube - new giant dinosaur species found in SA

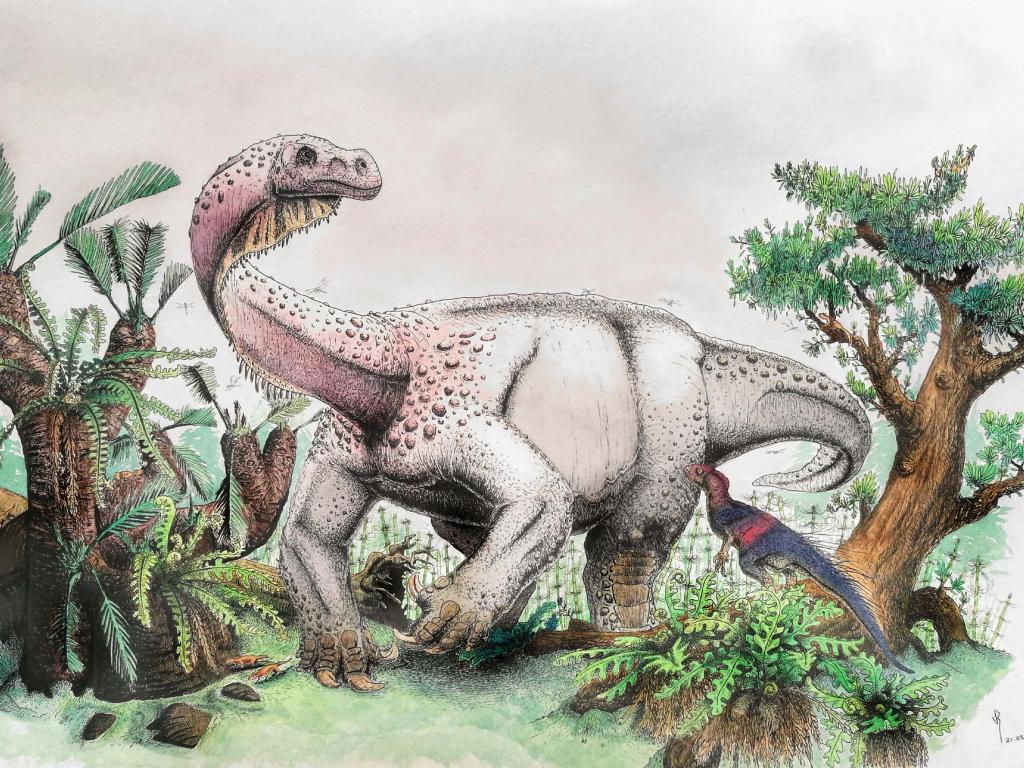

The Highland Giant: Artist Viktor Rademacher's reconstruction of what Ledumahadi mafube may have looked like. Picture credit: Viktor Rademacher

A new species of a giant dinosaur has been found in the Free State Province. The plant-eating dinosaur, named Ledumahadi mafube, weighed 12 tonnes and stood about four metres high at the hips. The name Ledumahadi mafube means "a giant thunderclap at dawn" in Sesotho, a nod to the appearance of the animal at the beginning of the age of the "thunder lizards".

An international team of scientists from the University of Cape Town (UCT), University of the Witwatersrand, Oxford University, and the South African National Museum have described this plant eating dinosaur was the largest land animal alive on earth when it lived, nearly 200 million years ago. It was roughly double the size of a large African elephant. Associate Professor Emese Bordy, from the Department of Geological Sciences at UCT was part of the team which made the description and recently published the findings in the journal Current Biology.

The dinosaur’s name, Ledumahadi mafube, is Sesotho for “a giant thunderclap at dawn” (Sesotho is one of South Africa’s 11 official languages and an indigenous language in the area where the dinosaur was found).

Ledumahadi lived in the area around Clarens, in the Free State. This is currently a scenic mountainous region, but looked much different 200 million years ago, with a flat, semi-arid landscape and shallow, intermittently dry streambeds. It was the work of UCT palaeoscientist, Associate Professor Bordy to tell the story of the ancient environment that sustained this giant dinosaur, and to relate the rocks that host the fossils to their global counterparts. According to Bordy "back then the area around Clarens looked a lot more like the current region around Musina in the Limpopo Province of South Africa, or South Africa’s central Karoo.” The story of this ancient environment is written in the Jurassic rock layers that are found in Lesotho and around it, in South Africa. "I have been studying the geology and palaeontology of this southern African Jurassic park for the past 16 years" says Bordy. "Every new discovery we make is a new, exciting puzzle piece that helps us tell the story of this 200-million-year-old complex ecosystem with more clarity. A few months ago, we published on another puzzle piece after my research team discovered a set of footprints made by a meat-eater, about 8 to 9-metre-long dinosaur. That megatheropod quite possibly preyed on the herbivorous Ledumahadi.

Minister of Science and Technology Mmamoloko Kubayi-Ngubane says the discovery of this dinosaur underscores just how important South African palaeontology is to the world.

“Not only does our country hold the Cradle of Humankind, but we also have fossils that help us understand the rise of the gigantic dinosaurs. This is another example of South Africa taking the high road and making scientific breakthroughs of international significance on the basis of its geographic advantage, as it does in astronomy, marine and polar research, indigenous knowledge, and biodiversity,” says Kubayi-Ngubane.

Ledumahadi is closely related to other gigantic dinosaurs from Argentina that lived at a similar time, which reinforces that the supercontinent of Pangaea was still assembled in the Early Jurassic. “It shows how easily dinosaurs could have walked from Johannesburg to Buenos Aires at that time,” says Wits University Palaeontologist, Professor Johan Choiniere.

Ledumahadi is one of the closest relatives of sauropod dinosaurs. Sauropods, weighing up to 60 tonnes, include well-known species like Brontosaurus. All sauropods ate plants and stood on four legs, with a posture like modern elephants. Ledumahadi evolved its giant size independently from sauropods, and although it stood on four legs, its forelimbs would have been more crouched. This caused the scientific team to consider Ledumahadi an evolutionary “experiment” with giant body size.

Ledumahadi’s fossil tells a fascinating story not only of its individual life history, but also the geographic history of where it lived, and of the evolutionary history of sauropod dinosaurs.

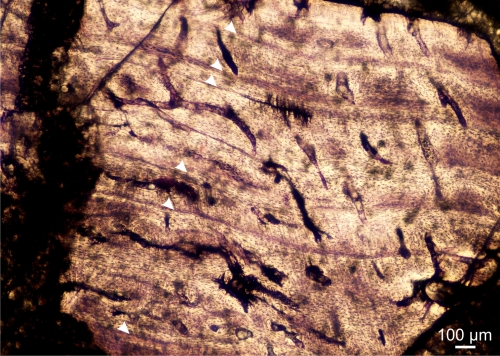

Closely spaced growth rings at the periphery is showing that the animal is an adult and that only a little bone tissue was deposited between the annually deposited growth rings, showing decreased growth rate.

“The first thing that struck me about this animal is the incredible robustness of the limb bones,” comments lead author, Dr Blair McPhee. “It was of similar size to the gigantic sauropod dinosaurs, but whereas the arms and legs of those animals are typically quite slender, Ledumahadi’s are incredibly thick. To me this indicated that the path towards gigantism in sauropodomorphs was far from straightforward, and that the way that these animals solved the usual problems of life, such as eating and moving, was much more dynamic within the group than previously thought.”

Ledumahadi Mafube is the first of the true giant sauropods of the Jurassic. Credit: Wits University

The research team developed a new method, using measurements from the “arms” and “legs” to show that Ledumahadi walked on all fours, like the later sauropod dinosaurs, but unlike many other members of its own group alive at its time such as Massospondylus. The team also showed that many earlier relatives of sauropods stood on all fours, that this body posture evolved more than once, and that it appeared earlier than scientists previously thought.

“Many giant dinosaurs walked on four legs but had ancestors that walked on two legs. Scientists want to know about this evolutionary change, but amazingly, no-one came up with a simple method to tell how each dinosaur walked, until now,” adds Professor Roger Benson.

By analysing the fossil’s bone tissue through osteohistological analysis, Dr Jennifer Botha-Brink from the South African National Museum in Bloemfontein established the animal’s age.

“We can tell by looking at the fossilised bone microstructure that the animal grew rapidly to adulthood. Closely-spaced, annually deposited growth rings at the periphery show that the growth rate had decreased substantially by the time it died,” says Dr Botha-Brink. This indicates that the animal had reached adulthood.

“It was also interesting to see that the bone tissues display aspects of both basal sauropodomorphs and the more derived sauropods, showing that Ledumahadi represents a transitional stage between these two major groups of dinosaurs.”

“South Africa employs some of the world’s top palaeontologists and it was a privilege to be able to build a working group with them and leading researchers in the UK,” explains Professor Choiniere, who recently emigrated from the USA to South Africa. “Dinosaurs did not observe international boundaries and it’s important that our research groups don’t either.”

Link to the journal article