Namibian fieldtripping in search of old photographs and elusive quiver trees

From Charles Darwin’s grand voyage on the HMS Beagle to RA Dyer’s southern African wanderings in search of rare cycad species, botanical research is rooted in exploration. My own ambitions fall well short of the above, but I nevertheless aspire to squeeze as much adventure out of my job as possible. Thanks largely to amenable leadership and with the help of some careful planning one can turn almost any outing into an opportunity to explore the unknown. Such was the case with the latest foray into Namibia.

The existing plan was some very necessary vacation-time in Namibia, camping and rock-climbing at Spitzkoppe, a striking 400 m high granite batholith NW of Windhoek. All that was needed was some research to conduct in the area in order to take advantage of my northerly latitudinal position and draw out my Namibian stay, thus avoiding the soggy end to winter in Cape Town. Not one but two research projects came to the rescue. The first was to supplement a collection of repeat photographs taken by anthropologist Dr Rick Rohde and Prof. Timm Hoffman, Director of the Plant Conservation Unit (PCU). This would contribute to the ‘Future Pasts’ project which is a cross-disciplinary research project exploring understandings and practices of sustainability in West Namibia, and funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council. The second was the continuation of tissue collection from the iconic arborescent succulent species Aloidendron dichotomum (commonly known as the quiver tree or kokerboom) and its sub-species A. ramosissima. This was being done on behalf of Randall Josephs, an MSc student who is working on the genetics of the species and hoping to understand how populations are related and have shifted in the region over millennia.

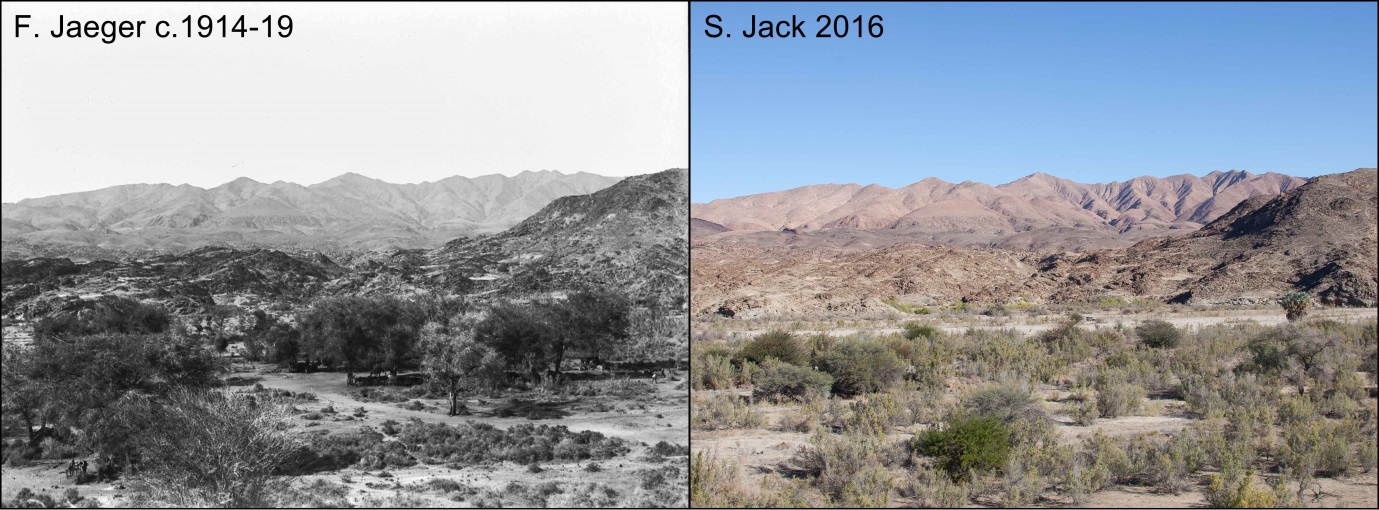

Matched repeat of the Swakop River north of Langer Heinrich showing how the river bed used to be utilised as a thoroughfare and for grazing/browsing in the early 1900s. A century later and the establishment of the Namib-Naukluft National Park and curtailed entry due to the establishment of the Langer Heinrich Uranium Mine has resulted in the disappearance of large trees and low scrub and the influx of Tamarisk sp.

Both projects required visiting remote areas of Namibia’s western Desert biome. Historical photographs from early travellers and diamond miners were located on the western and northern sides of the Brandberg massif, and at Langer Heinrich and Kries se Rus – all hyper-arid sites with sparse vegetation typified by leaf and stem succulent species, as well as a few oddities like the remarkable Welwitchia mirabilis and Cyphostemma curorii. The repeat photographs indicated very little change in these areas, besides in the drainage lines where there has perhaps been a slightly thickening up of bush and trees. Of the handful of photographs containing A. dichotomum, there seemed to be mixed fortunes, with some populations (such as the one at Kries se Rus) largely senescent and dying, while others (such as on the Brandberg plains) were holding steady. More historical photographs from the 20th century are needed for us to form a clearer picture of how population dynamics have changed.

Matched photo of Welwitchias. Alluvial gravel plains on the south-western side of the Brandberg. A scorched and desolate landscape where only Welwitchia mirabilis can survive, and seemingly quite stable populations exist.

Next on the agenda was further sampling of A. dichotomum and sub-species A. ramosissima populations at the south-western extremity of the Namibian distribution, and south-eastern South African distribution. Finding such populations would take me on a journey of several hundred kilometres into some of Namibia’s most remote and harshest environments. The first leg was undertaken from east of Luderitz and followed an access-restricted water infrastructure road north-east to the southern extent of the Namib sand sea, then back south-east along faint tracks past the impressive Kirchberg, Glockenberg and Dik Willem inselberg. The landscape surrounding these mountains can fairly be described as an utterly desolate moonscape, but also hauntingly beautiful due to the sweeping undisturbed views, the stillness and nakedness of the landscape. Only the hardiest of plants and animals manage to survive here, positioned in a climatic no-mans land between the upper reaches of the southern winter rainfall zone and southern reaches of the northern summer rainfall zone. A. dichotomum is one such species, surviving from water stored in its’ fleshy stem, branches and leaves. It and other plants probably rely not on rainfall, but on heavy fogs which frequently roll in from the cold Atlantic Ocean to the west.

Southern Namib-Naukluft landscape: Vastness and desolation on the southern edge of the Namib Desert.

Fairy circles on the flanks of the Dik Willem inselberg. The formation of these circular clearings is currently a hot topic in the natural sciences; the two prevailing theories suggest they are either maintained by the activity of the sand termite, Psammotermes sp. or are due to self-organisation by vegetation.

After making it safely back to the comparative bustle of Aus and sampling the southern Kuckhaus Mountains thanks to an invitation from Mr Piet Swiegers, the owner of Klein Aus Vista, it was southwards again and on to the diamond mining town of Oranjemund. There I met Mr Wayne Handley, Ministry of Environment and Tourism officer in charge of the Sperrgebiet. Mr Handley and his field ranger Paulus provided invaluable guidance on the network and condition of tracks in the Sperrgebiet. After clearing security - a non-trivial and lengthy exercise given active diamond mining along large stretches of the Atlantic coastline and Gariep River – I headed into the southern section of the Sperrgebiet. Despite being classified as desert, the eastern mountainous areas of the southern Sperrgebiet contained considerably more vegetation than similar longitudes to the north. This southerly position is more firmly located within the northern extremity of the winter rainfall zone and therefore intercepts more reliable rainfall to supplement the regular fogs that probably account for most of the received moisture.

Besides certain areas bordering the Gariep River, A. dichotomum is absent from the southern portion of the Sperrgebiet. Instead, its sub-species A. ramosissima - pictured here in the Aurus Mountains - is thriving and collectively this is probably the region with the greatest population densities for this sub-species.

While A. dichotomum was largely absent from the southern Sperrgebiet, I managed to find numerous large populations of A. ramosissima on rocky outcrops and mountains. This area appears to be highly suitable to the sub-species, which has a much restricted distribution compared to A. dichotomum. The poor overlap between A. dichotomum and its sub-species is something of a mystery that the genetic work might be able to shed some light on. While both species are adapted for survival in hyper-arid environments, the low growing and thinly branched A. ramosissima is more strictly tied to the winter rainfall zone, suggesting an affinity for more reliable winter moisture from both rainfall and fog. A. dichotomum’s more upright single stemmed architecture has possibly aided it in ‘escaping’ the confines of the winter rainfall zone, but the mechanisms for this are unclear.

Quiver tree populations such as this one on the farm Lemoenpoort southwest of Prieska are doing very well, possibly due to increased temperatures as a result of global warming.

After several days of solitude in the Sperrgebiet, it was time to say farewell to Namibia and head south-east back into the Northern Cape and along the Gariep River down to Prieska, sampling along the way. Stops included areas around Goodhouse, Pofadder, Onseepkans, Pella, Kakamas, Riemvasmaak and Keimoes, then a swathe of sampling en route to and surrounding Kenhardt. Despite the diseased state of the ‘official’ quiver tree ‘forest’ at Kenhardt, the surrounding areas contain numerous thriving populations, suggesting a bright future for quiver trees in this area (and begging the question, what is causing them to do so well here?). The last of the sampling took me via Groblershoop, past the abandoned asbestos mining settlements of Koegas and Westerberg to the very south-easternmost populations to the east of Prieska. These populations also seem to be mostly thriving and could mean that anthropogenic warming to date might be benefitting these populations by a) increasing photosynthetic rates due to higher ambient temperatures, and b) reducing incidences of frost. What is clear is that there are many open questions regarding the quiver tree and a lot of work still to be done!

~ Article & images supplied by Sam Jack (PCU)