We conduct problem-driven research to try to understand conservation conflicts from ecological, social and governance perspectives. Read more about our various projects below.

-

African wild dog reintroductions

African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) are one of the most endangered carnivores in southern Africa. Direct persecution, prey decline and habitat loss and fragmentation all contributed to a rapid decline in this species’ population size and distribution during the 20th Century. Following a thorough population viability analysis in the late 1990s the decision was taken to manage the South African population as a metapopulation. This involved the reintroduction of packs to small, fenced protected areas and the subsequent transfer of individuals or small groups between reserves to avoid inbreeding. A key component of successful metapopulation management is post-release monitoring to provide data on the determinants of reintroduction success and failure, particularly when establishing new populations. This study aimed to provide information on the post-release behaviour and movements of a pack of eight African wild dogs introduced to the Northern Tuli Game Reserve in eastern Botswana in February 2017.

African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) are one of the most endangered carnivores in southern Africa. Direct persecution, prey decline and habitat loss and fragmentation all contributed to a rapid decline in this species’ population size and distribution during the 20th Century. Following a thorough population viability analysis in the late 1990s the decision was taken to manage the South African population as a metapopulation. This involved the reintroduction of packs to small, fenced protected areas and the subsequent transfer of individuals or small groups between reserves to avoid inbreeding. A key component of successful metapopulation management is post-release monitoring to provide data on the determinants of reintroduction success and failure, particularly when establishing new populations. This study aimed to provide information on the post-release behaviour and movements of a pack of eight African wild dogs introduced to the Northern Tuli Game Reserve in eastern Botswana in February 2017.

-

Biogaps

Gaps in our knowledge of where animal species occur can impede our ability to effectively manage and conserve them. This is especially true in areas where planned, large-scale landscape changes often have major impacts on the animals living within them. The Karoo region of South Africa has been earmarked for shale gas fracking and uranium mining. However concerns have been raised over the potentially negative effects these developments will have on the region’s biodiversity. In 2016, to address large gaps in our knowledge of the Karoo’s ecology in the Shale Gas Exploration Area (SGEA), the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) initiated a multi-institutional project named BioGaps. We worked as part of Biogaps to collect baseline data on the spatial diversity and community structure of mammals across 30 sites in the SGEA. We aimed to provide baseline survey data that could then be used to support government decision-making. Read more.

-

Cape Peninsula baboons

Although conflict between humans and wildlife on the urban edge is a global phenomenon, baboons are undoubtedly one of the most challenging animals to share space with. They are strong, agile and dexterous which allows them to scale an apartment block and unzip a bag with equal panache. They’re also social and so can learn from each other as they search for new food sources in an ever changing world. It’s in this context that iCWild’s long history of baboon research began.

Although conflict between humans and wildlife on the urban edge is a global phenomenon, baboons are undoubtedly one of the most challenging animals to share space with. They are strong, agile and dexterous which allows them to scale an apartment block and unzip a bag with equal panache. They’re also social and so can learn from each other as they search for new food sources in an ever changing world. It’s in this context that iCWild’s long history of baboon research began.

-

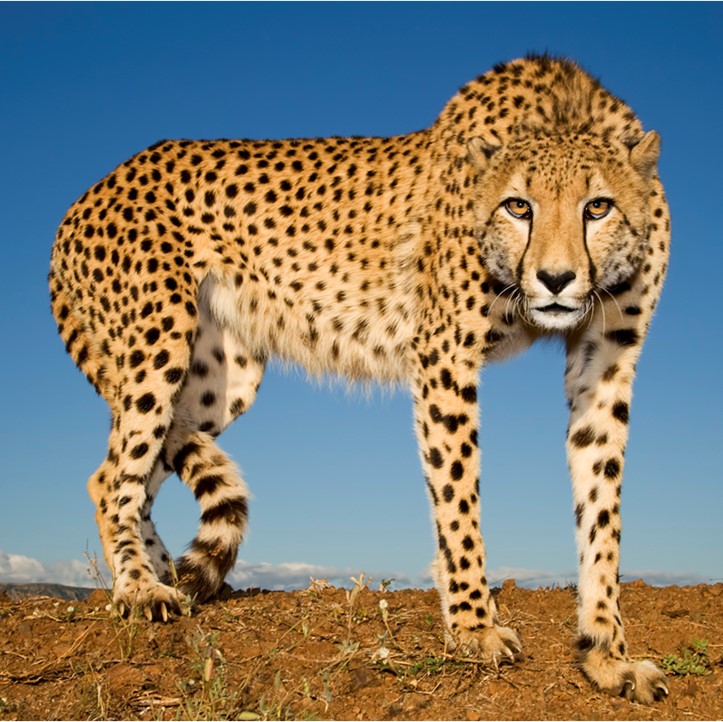

Cheetah metapopulation

Since 1965, wild cheetahs have been reintroduced onto 54 fenced reserves in South Africa. In 2009, the Carnivore Conservation Project of the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) identified the requirement for the establishment of a managed metapopulation to ensure the long term genetic and demographic integrity of these isolated populations. We partnered with EWT in 2018 to investigate the potential for metapopulation management to increase the resident range of wild Cheetahs in Africa.

Since 1965, wild cheetahs have been reintroduced onto 54 fenced reserves in South Africa. In 2009, the Carnivore Conservation Project of the Endangered Wildlife Trust (EWT) identified the requirement for the establishment of a managed metapopulation to ensure the long term genetic and demographic integrity of these isolated populations. We partnered with EWT in 2018 to investigate the potential for metapopulation management to increase the resident range of wild Cheetahs in Africa.

-

Eco-estates

Estates, and eco-estates in particular, are becoming progressively more common in South Africa. Yet, there is little research into the effects such estates have on the environment. This project will provide information regarding the ability of an eco-estate to maintain faunal communities, by comparing Atlantic Beach Estate, located in the ecologically-sensitive fynbos in South Africa’s Western Cape, to Blaauwberg, a neighbouring nature reserve. We aim to quantify the differences in faunal biodiversity between the estate and the nature reserve, comparing differences in the total number of species (species richness), and how the number of individuals is divided among the number of species (evenness). We will use camera traps to monitor large mammals, and sample small mammals using Sherman traps (a rectangular metal trap which captures rodents without causing injury). We will also sample birds via visual observation and vocalisations. We will supplement this ecological data with resident surveys to understand people’s perceptions of nature on the estate. Read more.

-

Human-baboon coexistence

While residents and wildlife managers across Africa typically seek to exclude baboons from residential areas, the residents of Rooiels, a coastal village and registered urban conservancy near Cape Town, South Africa, have opted to coexist with the local wild baboon troop. This unique situation provides the opportunity to understand the factors that make coexistence possible from both a human and baboon perspective, and can yield insights into how to minimise and mitigate human-baboon conflict in urban communities elsewhere.

While residents and wildlife managers across Africa typically seek to exclude baboons from residential areas, the residents of Rooiels, a coastal village and registered urban conservancy near Cape Town, South Africa, have opted to coexist with the local wild baboon troop. This unique situation provides the opportunity to understand the factors that make coexistence possible from both a human and baboon perspective, and can yield insights into how to minimise and mitigate human-baboon conflict in urban communities elsewhere.

-

Illegal leopard and skin trade

The primary threat to leopards in southern Africa is the demand for their skins for ceremonial dress. In South Africa, members of the Nazareth Baptist ‘Shembe’ Church have adopted the Zulu custom of chiefs and royals wearing leopard skins as symbols of power and prestige. What was once the privilege of a select few is now common practice among the Shembe’s rapidly expanding congregation (>1 million members). Mark-resight surveys suggest that approximately 1,500 to 2,500 leopards are killed annually to meet the demand for skins, with more than 15,000 illegal skins already in circulation among the Shembe. It is undoubtedly the largest collection of illegal wildlife contraband anywhere in the world and it is putting tremendous pressure on regional leopard populations. In partnership with Panthera and the South African Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), we are using genetic forensic techniques to demonstrate the geographic extent of the skin trade and pinpoint the leopard populations most affected. We are also investigating both Zulu and Shembe perspectives on faux furs. With this information, we can compel conservation authorities to act. More importantly, we will be able to prioritise the deployment of scarce resources to the most critical areas.

The primary threat to leopards in southern Africa is the demand for their skins for ceremonial dress. In South Africa, members of the Nazareth Baptist ‘Shembe’ Church have adopted the Zulu custom of chiefs and royals wearing leopard skins as symbols of power and prestige. What was once the privilege of a select few is now common practice among the Shembe’s rapidly expanding congregation (>1 million members). Mark-resight surveys suggest that approximately 1,500 to 2,500 leopards are killed annually to meet the demand for skins, with more than 15,000 illegal skins already in circulation among the Shembe. It is undoubtedly the largest collection of illegal wildlife contraband anywhere in the world and it is putting tremendous pressure on regional leopard populations. In partnership with Panthera and the South African Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), we are using genetic forensic techniques to demonstrate the geographic extent of the skin trade and pinpoint the leopard populations most affected. We are also investigating both Zulu and Shembe perspectives on faux furs. With this information, we can compel conservation authorities to act. More importantly, we will be able to prioritise the deployment of scarce resources to the most critical areas.

-

Karoo predators

With the abundance and concentration of food sources (in the form of sheep), small-livestock farms directly affect the ranging patterns and behaviour of predators. They also impact wildlife species richness and relative abundance. In the Karoo region of South Africa, farmers have responded to the threat of livestock predation through sustained hunting programs and live trapping of predators, mainly of black-backed jackal, caracal and chacma baboons. Our research aims to develop our understanding of the characteristics, determinants and management of farmer-predator conflict.

With the abundance and concentration of food sources (in the form of sheep), small-livestock farms directly affect the ranging patterns and behaviour of predators. They also impact wildlife species richness and relative abundance. In the Karoo region of South Africa, farmers have responded to the threat of livestock predation through sustained hunting programs and live trapping of predators, mainly of black-backed jackal, caracal and chacma baboons. Our research aims to develop our understanding of the characteristics, determinants and management of farmer-predator conflict.

-

Karoo rewilding

With the establishment of the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) in the Karoo, in the Northern Cape province of South Africa, a unique opportunity arose to study the impacts of landscape-scale land use change on mammal populations. The aim of this project is to look at how sheep removal and the establishment of a protected area within a predominantly small livestock farming area will impact local mammal populations (e.g., rats, mice, foxes, jackals, etc.) in the SKA region.

With the establishment of the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) in the Karoo, in the Northern Cape province of South Africa, a unique opportunity arose to study the impacts of landscape-scale land use change on mammal populations. The aim of this project is to look at how sheep removal and the establishment of a protected area within a predominantly small livestock farming area will impact local mammal populations (e.g., rats, mice, foxes, jackals, etc.) in the SKA region.

-

Khayelitsha Rodent Study

The Khayelitsha Rodent Study (KRS) is a joint initiative between iCWild and the Centre for Social Science Research (CSSR) focusing on the socio-economic aspects of rodent infestation in a poor community in Cape Town, South Africa, and the related implications for the use of rodenticides and other poisons. The study originated in response to the controversy over a Public Works Programme (PWP) run by the Khayelitsha Environmental Health Unit in which previously unemployed people were hired to set cage traps in people’s homes and then drown the captured rats. The Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA) threatened legal action (because drowning animals is illegal) and the PWP resorted back to using poison. We explored how people in Khayelitsha felt about the issue and on the dangers posed by poison to people and wildlife.

-

Kwazulu-Natal mesocarnivores

Conflict between humans and mesocarnivores is rampant given the risk the animals present to disease transmission (e.g., rabies), and their dietary preference for livestock. The resultant lack of tolerance of mesocarnivores in urban and agricultural lands, means that protected areas (PAs) are often presumed to support a higher diversity and abundance of mesocarnivores. Yet this may not be the case, as PAs face a wide variety of threats, such as invasive species, human-wildlife conflict and wildlife and environmental exploitation along the periphery, which can reduce their conservation potential. We used camera traps to investigate mesocarnivore species richness and occupancy across seven sites in Kwazulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa.

Conflict between humans and mesocarnivores is rampant given the risk the animals present to disease transmission (e.g., rabies), and their dietary preference for livestock. The resultant lack of tolerance of mesocarnivores in urban and agricultural lands, means that protected areas (PAs) are often presumed to support a higher diversity and abundance of mesocarnivores. Yet this may not be the case, as PAs face a wide variety of threats, such as invasive species, human-wildlife conflict and wildlife and environmental exploitation along the periphery, which can reduce their conservation potential. We used camera traps to investigate mesocarnivore species richness and occupancy across seven sites in Kwazulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa.

-

Leopard camera trapping

Recent technological and statistical advances have improved our ability to monitor leopards using camera traps. As a result, these cameras are now widely used to determine leopard densities, and to infer population health. However, to determine densities accurately the camera traps need to be deployed in relatively intensive, high-density grids. This makes the method best suited to surveys of small areas. Through a large-scale camera trapping exercise in the Kruger National Park, South Africa, we are exploring potential indices that could provide a more accurate indication of population health than density alone. These indices may also be possible to obtain from less dense camera trap arrays, making camera trapping more feasible across larger areas.

Recent technological and statistical advances have improved our ability to monitor leopards using camera traps. As a result, these cameras are now widely used to determine leopard densities, and to infer population health. However, to determine densities accurately the camera traps need to be deployed in relatively intensive, high-density grids. This makes the method best suited to surveys of small areas. Through a large-scale camera trapping exercise in the Kruger National Park, South Africa, we are exploring potential indices that could provide a more accurate indication of population health than density alone. These indices may also be possible to obtain from less dense camera trap arrays, making camera trapping more feasible across larger areas.

-

Namaqua PEACE sub-project

One of the methods used to deter predators in Namaqualand is livestock guarding dogs. While there are more than 40 different breeds of livestock guarding dogs worldwide, Anatolian Shepherds are commonly used in South Africa due to climatic similarities with the Turkish Anatolian Plateau where the breed originated. The dogs are perceived to be effective at reducing livestock losses (most studies of their efficacy rely solely on farmer recollection and anecdotes), but they are also large enough to act as predators, with little known about their ecological impacts. We wanted to better understand the dog’s impacts on local biodiversity and whether or not they were effectively changing predator diets in the region.

One of the methods used to deter predators in Namaqualand is livestock guarding dogs. While there are more than 40 different breeds of livestock guarding dogs worldwide, Anatolian Shepherds are commonly used in South Africa due to climatic similarities with the Turkish Anatolian Plateau where the breed originated. The dogs are perceived to be effective at reducing livestock losses (most studies of their efficacy rely solely on farmer recollection and anecdotes), but they are also large enough to act as predators, with little known about their ecological impacts. We wanted to better understand the dog’s impacts on local biodiversity and whether or not they were effectively changing predator diets in the region.

-

Namibian communal conservancies

The community based natural resources management (CBNRM) system, which links conservation to poverty alleviation through sustainable use of natural resources, is a key development strategy for rural Namibia. The overall goal of this research is to better understand and tackle conservation conflicts in Namibian communal conservancies. By better integrating the underpinning social context with the material impacts and evaluation of conflicts across communal conservancies, we hope to enhance effective conflict management and long-term conservation benefits.

The community based natural resources management (CBNRM) system, which links conservation to poverty alleviation through sustainable use of natural resources, is a key development strategy for rural Namibia. The overall goal of this research is to better understand and tackle conservation conflicts in Namibian communal conservancies. By better integrating the underpinning social context with the material impacts and evaluation of conflicts across communal conservancies, we hope to enhance effective conflict management and long-term conservation benefits.

-

Sharks in False Bay

Sharks ranging in close proximity to urban areas are threatened by direct exploitation, bycatch, pollution and habitat degradation. In order to conserve important apex predators in these areas we need to better understand how they use the coastline, what drives their movement patterns, and how best to balance their needs with those of coastal human populations. We work along the False Bay coastline in Cape Town, South Africa to develop a robust understanding of sharks in the False Bay ecosystem. We not only aim to contribute to ecological theory, but to inform species management and conservation.

Sharks ranging in close proximity to urban areas are threatened by direct exploitation, bycatch, pollution and habitat degradation. In order to conserve important apex predators in these areas we need to better understand how they use the coastline, what drives their movement patterns, and how best to balance their needs with those of coastal human populations. We work along the False Bay coastline in Cape Town, South Africa to develop a robust understanding of sharks in the False Bay ecosystem. We not only aim to contribute to ecological theory, but to inform species management and conservation.

-

Transfrontier leopards

Wildlife authorities in southern Africa do not know enough about the status of leopard populations to formulate effective management policies. This oollaboration between iCWild, Panthera, Peace Parks Foundation, SANBI, the South African Scientific Authority, and regional wildlife agencies, aims to address this information deficit.

Wildlife authorities in southern Africa do not know enough about the status of leopard populations to formulate effective management policies. This oollaboration between iCWild, Panthera, Peace Parks Foundation, SANBI, the South African Scientific Authority, and regional wildlife agencies, aims to address this information deficit.

-

Urban Caracal Project

Humans drastically impact the environment in multiple ways that have downstream consequences for biodiversity conservation. Yet few studies investigate the many ways that urbanisation influences wildlife populations so that threats can be mitigated when possible. By examining the behavioural and genetic response of caracals in the isolated Cape Peninsula, South Africa, and by quantifying the potential consequences of urban foraging, we want to learn more about caracals, and whether (and how) they are adapting to increasingly human-dominated landscapes.

Humans drastically impact the environment in multiple ways that have downstream consequences for biodiversity conservation. Yet few studies investigate the many ways that urbanisation influences wildlife populations so that threats can be mitigated when possible. By examining the behavioural and genetic response of caracals in the isolated Cape Peninsula, South Africa, and by quantifying the potential consequences of urban foraging, we want to learn more about caracals, and whether (and how) they are adapting to increasingly human-dominated landscapes.

-

Virtual fences

Virtual fences are proving to be a successful, non-invasive and cost-effective way of managing the movement of livestock and wildlife. For instance, virtual boundaries have been used to manage cattle grazing across pastures, and alongside busy roads to prevent road-related wildlife deaths and injuries. Our aim is to assess whether a virtual fence being used in Gordon’s Bay, South Africa, is effective at managing troop movement patterns and minimising human-baboon conflict.

Virtual fences are proving to be a successful, non-invasive and cost-effective way of managing the movement of livestock and wildlife. For instance, virtual boundaries have been used to manage cattle grazing across pastures, and alongside busy roads to prevent road-related wildlife deaths and injuries. Our aim is to assess whether a virtual fence being used in Gordon’s Bay, South Africa, is effective at managing troop movement patterns and minimising human-baboon conflict.